Introduction

Balangoda Manawaya represents one of the most fascinating and important prehistoric discoveries in Sri Lanka. These ancient human remains, found in Balangoda, have been crucial in understanding the early human presence in South Asia. The discovery of the Balangoda Man sheds light on the evolutionary journey of humanity, providing critical insights into the life, culture, and behavior of prehistoric populations.

Sri Lanka’s rich history is often highlighted by its ancient civilizations, but Balangoda Manawaya presents an even older legacy. The study of these ancient humans has significantly advanced our understanding of the transition from prehistory to the development of sophisticated human societies. In this article, we’ll explore the discovery, significance, lifestyle, culture, and broader historical context of Balangoda Manawaya, as well as its importance in both archaeological and anthropological studies.

Chapter 1 The Discovery of Balangoda Manawaya

The story of the Balangoda Manawaya begins in the Balangoda region, a hilly district in south-central Sri Lanka. This region became the focal point of prehistoric studies when skeletal remains were discovered in the late 20th century. Renowned archaeologist Dr. P.E.P. Deraniyagala, who made significant contributions to the understanding of prehistoric humans in Sri Lanka, spearheaded the excavation and study of these ancient remains.

The human fossils, along with tools and other artifacts, were found in various caves in and around Balangoda. The Fa Hien Cave, Batadombalena Cave, and Belilena Cave are among the most notable sites. Radiocarbon dating estimates these skeletal remains to be as old as 38,000 years, making Balangoda Manawaya one of the earliest known humans in the region. These discoveries were significant because they provided evidence of human activity during the Pleistocene epoch, marking a pivotal moment in Sri Lankan prehistory.

Chapter 2 Significance of Balangoda Manawaya in Prehistoric Studies

The Balangoda Manawaya discoveries are essential for several reasons. Firstly, they provide valuable evidence of the early human presence in Sri Lanka and South Asia. These remains indicate that humans had settled in the region far earlier than previously thought. This challenges previous assumptions that ancient human migration primarily occurred in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East, showing that South Asia played a vital role in human evolution.

Moreover, the skeletal remains and associated tools indicate that Balangoda Manawaya were anatomically modern humans, also known as Homo sapiens. These early humans had physical features similar to those of modern-day Sri Lankans but exhibited slight variations, such as more robust builds and larger craniums. This suggests that they had adapted to the environment and lifestyle of prehistoric Sri Lanka.

The tools discovered alongside the remains are crucial artifacts. Made of stone and bone, these tools suggest that Balangoda Manawaya were hunter-gatherers who used simple yet effective methods for survival. The tools also reflect their knowledge of the local environment, as they were crafted from materials found in the surrounding landscape.

Chapter 3 Physical Characteristics of Balangoda Man

Balangoda Man is often recognized for his distinct physical features. Anthropological studies have shown that the Balangoda people were relatively short in stature, with males averaging around 5 feet 3 inches (1.6 meters) and females being slightly shorter. They possessed a robust build, which was well-suited to the demands of a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

One of the most striking features of Balangoda Man was the large cranium, which housed a relatively large brain. This feature is significant because it indicates advanced cognitive abilities. Additionally, the skulls showed pronounced brow ridges and wide nasal apertures, which might have been adaptations to the climatic conditions of prehistoric Sri Lanka.

Chapter 4 Lifestyle and Culture of Balangoda Manawaya

The Balangoda Manawaya were primarily hunter-gatherers, relying on the rich biodiversity of Sri Lanka’s forests for sustenance. They hunted animals such as deer, wild boar, and small mammals, using stone tools and primitive weapons such as spears. They also gathered edible plants, fruits, and nuts, which were abundant in the region’s dense forests.

One of the most significant aspects of the Balangoda Manawaya lifestyle was their use of caves as shelter. The Fa Hien Cave, in particular, provided refuge for these prehistoric people, with evidence of human occupation dating back nearly 40,000 years. The caves not only offered protection from the elements but also served as communal spaces for social interaction and cultural expression.

The Balangoda Manawaya are believed to have engaged in rudimentary forms of art and ritual practices. Evidence of ochre use suggests that they may have decorated their bodies or objects with pigments, indicating a form of symbolic expression. Additionally, the presence of burial sites within the caves suggests that the Balangoda Manawaya practiced some form of funerary rites, highlighting a level of cultural and spiritual development.

Chapter 5 Tools and Technology

The tools used by the Balangoda Manawaya were primarily made from stone and bone. These tools were simple yet effective, designed for specific tasks such as hunting, cutting, and processing food. The most common types of tools found at Balangoda sites include stone scrapers, choppers, and points, which were likely used for hunting and butchering animals.

The technology of Balangoda Manawaya reflects their deep understanding of the natural world. They were able to craft tools from locally available materials, such as quartz and chert, and adapt their techniques to suit the environment. The tools show signs of wear and re-sharpening, indicating that the Balangoda Manawaya maintained and reused their implements, demonstrating resourcefulness and efficiency in their tool-making practices.

Chapter 6 The Environmental Context

The environment in which the Balangoda Manawaya lived was vastly different from present-day Sri Lanka. During the Pleistocene epoch, the region experienced significant climatic changes, including fluctuations in temperature and rainfall. These environmental shifts influenced the availability of resources, such as food and water, and likely shaped the behavior and survival strategies of the Balangoda people.

The Balangoda Manawaya were well-adapted to these changing conditions. They occupied caves in the central highlands, which provided a stable and sheltered environment amidst the varying climate. The surrounding forests and grasslands offered a diverse range of food sources, enabling the Balangoda Manawaya to sustain their hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Additionally, the proximity of the Balangoda region to waterways, such as rivers and streams, would have provided a consistent source of freshwater and facilitated the movement of people and goods. This access to water may have also influenced the development of early trade networks, as groups of prehistoric humans interacted with one another across the landscape.

Chapter 7 Interaction with Other Prehistoric Populations

The Balangoda Manawaya were not isolated; they likely interacted with other prehistoric populations both within Sri Lanka and beyond. Archaeological evidence suggests that early humans in Sri Lanka had contact with populations in South India, as similar tools and artifacts have been found in both regions. This interaction would have facilitated the exchange of knowledge, technology, and cultural practices.

Trade and migration between these regions may have played a significant role in the development of early human societies in South Asia. The similarities in tool technology and burial practices across these regions suggest that the Balangoda Manawaya were part of a larger network of prehistoric humans who shared common cultural traits and survival strategies.

Chapter 8 Legacy and Continuity

The legacy of Balangoda Manawaya continues to influence our understanding of Sri Lanka's prehistoric heritage. While the Balangoda Manawaya eventually transitioned into more advanced forms of human society, their impact on the development of Sri Lankan culture cannot be understated. The transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agricultural communities marks a significant shift in human history, and the Balangoda Manawaya played a key role in this evolution.

Many of the cultural and technological practices of the Balangoda Manawaya were passed down through generations, influencing the development of early agricultural societies in Sri Lanka. For example, their knowledge of the local environment and resource management likely contributed to the success of early farming communities.

Chapter 9 Current Research and Future Discoveries

The study of Balangoda Manawaya is ongoing, with new discoveries continuing to shed light on the lives of these ancient people. Advances in technology, such as DNA analysis and 3D scanning, have allowed researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the biology, culture, and behavior of Balangoda Manawaya.

Current research is focused on uncovering more about their diet, social structure, and interactions with other prehistoric populations. Additionally, further excavations in caves and other archaeological sites in the Balangoda region may reveal new information about the extent of their settlement and their influence on later human populations.

Conclusion

The Balangoda Manawaya represents a crucial chapter in the history of human evolution in South Asia. Their discovery has provided valuable insights into the lives of prehistoric humans and has challenged previous assumptions about the timeline of human migration and development in the region. The Balangoda Manawaya were not only skilled hunters and gatherers but also innovators who adapted to their environment and contributed to the cultural legacy of Sri Lanka.

As research continues, the story of Balangoda Manawaya will undoubtedly evolve, offering new perspectives on the origins of humanity in Sri Lanka and beyond. The ancient bones and tools unearthed in the caves of Balangoda serve as a reminder of our deep connection to the past and the enduring legacy of those who came before us.

Balangoda Man refers to hominins from Sri Lanka's late Quaternary period. The term was initially coined to refer to anatomically modern Homo sapiens from sites near Balangoda that were responsible for the island's Mesolithic 'Balangoda Culture'. The earliest evidence of Balangoda Man from archaeological sequences at caves and other sites dates back to 38,000 BP, and from excavated skeletal remains to 30,000 BP, which is also the earliest reliably dated record of anatomically modern humans in South Asia. Cultural remains discovered alongside the skeletal fragments include geometric microliths dating to 28,500 BP, which together with some sites in Africa is the earliest record of such stone tools.

Balangoda Man is estimated to have had thick skulls, prominent supraorbital ridges, depressed noses, heavy jaws, short necks and conspicuously large teeth. Metrical and morphometric features of skeletal fragments extracted from cave sites that were occupied during different periods have indicated a rare biological affinity over a time frame of roughly 16,000 years, and the likelihood of a partial biological continuum to the present-day Vedda indigenous people.

Sri Lankan skeletal and cultural discoveries

Compared to the earlier Sri Lankan fossils, the island's fossil records from around 40,000 BP onwards are much more complete. Excavated fossils of skeletal and cultural remains from this period provide the earliest records of anatomically modern Homo sapiens in South Asia, and some of the earliest evidence for the use of a specific type of stone tool.

The Fa Hien Cave in the Kalutara district in Sri Lanka, one of the largest caves on the island, has yielded some of the earliest such fossils. Radiometric dating from excavated charcoal samples indicated that the cave was occupied from 34,000 to 5,400 BP, a period that was found to be consistent with the occupational levels of some other caves on the island. Dates from cultural sequences at the cave suggested a slightly earlier settlement from 38,000 BP. The oldest skeletal remains unearthed from Fa Hien Cave were that of a child with an associated radiocarbon dating of 30,000 BP.

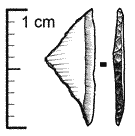

Caves in Batadomba lena, 460 m above sea level in the foothills of Sri Pada (Adam's Peak), have also yielded several important ancient remains. The first excavation of the cave floor in the late 1930s unearthed skeletal fragments of a child and several adults. Excavations in 1981 yielded more complete human skeletons from the sixth stratum (a layer of internally consistent sedimentary soil or rock) which were radiocarbon dated from associated charcoal samples to 16,000 BP. Excavations of the seventh stratum in the following year produced further human remains along with charcoal and 17 geometric microliths, i.e. 1–4 cm long triangular, trapezoid or lunate stone tools made of flint or chert that form, among other artifacts, the end points of hunting weapons such as spears and arrows. Radiometric tests on the charcoal placed the tools to around 28,500 BP.

Along with some sites in Africa that have also revealed geometric microliths from contexts earlier than 27,000 BP, those recovered from caves in Beli lena in Kitulgala and Batadomba lena, and from two coastal sites in Bundala have the earliest dates for geometric microliths in the world. The earliest date for the use of microlithic technology in India of 24,500 BP, in the Patne site in Maharashtra, only slightly postdates the first appearance in Sri Lanka. Such early evidence of microlithic industries in various sites in South Asia supports the view that at least some of these industries emerged regionally, perhaps to deal with challenging climatic, social or demographic conditions, rather than being brought in from elsewhere. In Europe, the earliest dates for microliths seem to start from around 12,000 BP, though there does appear to be a trend towards microlithic blade production from 20,000 BP.

Mesolithic sites in the Sabaragamuva and Uva provinces in Sri Lanka confirmed that microlithic technology continued on the island, albeit at a lower frequency, until the onset of the historical period, traditionally the 6th century BC. Cultural sequences at rock shelters showed that microliths were gradually replaced by other types of tools including grinding stones, pestles, mortars, and pitted hammers-stones towards the late Pleistocene, specifically 13,000-14,000 BP.

Other sites that have revealed ancient human skeletal fragments are the Beli lena cave and Bellanbandi Palassa in the Ratnapura district. Carbon samples corresponding to the fragments were dated to respectively 12,000 BP for the former site and 6,500 BP for the latter, suggesting that the island may have been relatively continuously occupied during this time frame.

Physical traits and cultural practices

Certain samples of Balangoda Man were estimated to be 174 cm tall for males and 166 cm tall for females, a significantly higher figure than modern day Sri Lankan populations. They also had thick skull-bones, prominent supraorbital ridges, depressed noses, heavy jaws, short necks and conspicuously large teeth.

Apart from the microliths, hand-axes from Meso-Neolithic times were discovered at Bellanbandi Palassa, which were manufactured from slabs extracted from the leg bones of elephants, and also daggers or celts made from sambar antler. From the same period, this and other sites have also yielded evidence of widespread use of ochre, domesticated dogs, differentiated use of space, inferred burials, and the strong use of fire.

Other cultural discoveries of interest from the meso-neolothic period included articles of personal ornamentation and animals utilised as food, e.g. fish bones, seashell-based beads and shell pendants, shark vertebra beads, lagoon shells, molluscan remains, carbonised wild banana, breadfruit epicarps, and polished bone tools.

The frequency at which the marine shells, shark teeth and shark beads occurred at the different cave sites suggested that the cave dwellers likely had direct contact with the coast around 40 km away; Beli lena also showed signs that salt had been brought back from the coast.

The microlithic tradition appears to have been contemporaneous with high mobility, the use of rainforest resources and adaptation to changing climate and environment. The discovery of geometric microliths at Horton Plains, located on the southern plateau of the central highlands of Sri Lanka, suggests that the area was visited by prehistoric humans from the Mesolithic period. One possible interpretation is that in their annual cycle of foraging for food, prehistoric hunter-gatherers that lived in lowland rock-shelters periodically visited the Horton Plains for hunting—possibly wild cattle, sambur and deer—and gathering foods such as wild cereals. While it was likely used as a temporary camp-site, Horton Plains does not appear to have been used for more permanent settlement. From the late Pleistocene and Holocene periods there is evidence for the use of several lowland rainforest plant resources including wild breadfruit and banana, and canarium nuts.

The transition from hunter-foraging to food production with domesticated cereals and other plants seems to have begun in some tropical regions at the beginning of the Holocene. Until then, humans probably exploited the Horton Plains wetland, grassland and rainforest resources using slash-and-burn techniques, and facilitated the growth of rice fields.

troglodyte, troglodyte meaning. troglodyte definition. what is a troglodyte. troglodyte 5e. define troglodyte. troglodyte niger. troglodyte song. troglodyte dnd troglodyte synonym.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)